Immigrant Student Finds Hope in Shirley Smith’s Classroom

CCD's business instructor Shirley Smith brings the real world into the classroom.

Shirley Smith was about to quit her teaching job at a Houston high school. A student had disrespected her and she felt like she couldn’t make a difference.

She had just called the principal to resign and was on hold. As Smith waited, she opened letters she’d received from students who’d been assigned to write to their favorite teacher.

Smith opened a letter from Eduardo, an immigrant from Guatemala. Eduardo had been struggling in America; he didn’t know English and had no friends. He was considering taking his life, he admitted in his letter until he took Smith’s class.

“’You talked about diversity and you sat with me and helped me with my assignment,’” Smith recalls him writing in the letter. “I obtained a Spanish translator to help him, and he received a 100 percent grade on an assignment in another class. He wrote, ’I want to thank you. You made me feel so special.’ I was reading that letter, and tears were streaming down my face. I didn’t quit that day.”

A Perfect Fit at Community College of Denver

Smith eventually did leave Houston, but she never quit teaching. She moved to Colorado and became an associate professor of business administration at Community College of Denver (CCD) in 2016. Her teaching style was a good fit at CCD, whose faculty have a reputation for being passionate and personable. Her ability to connect with students from all backgrounds made her valuable at a school with a minority-majority population.

Smith currently teaches Intro to Business and Business Communications and Business Communications.

“My philosophy is, ‘I teach as I learn,’” Smith says, who prefers to be in a chair next to a student rather than at a lectern in front of them. “I try not to just lecture, lecture, lecture; I do things to keep them engaged, keep things fun; I tell a lot of jokes.”

Smith often uses current events as her subject matter. For example, during the G7 Summit, she taught the class about tariffs and NAFTA. She also teaches students how to read the stock market.

“I love molding young minds,” Smith says. “Seeing them light up when they get it is so fulfilling.”

The Car Rides That Got Her to Business School

Smith grew up in rural Mississippi.

“I’m a country girl who wears shoes,” she answers with a laugh, when asked to describe herself, then talks about her father. “He put 10 kids through college without any grants or loans.”

When Smith was 11, she would ride in the car with her father to business meetings. He couldn’t read well, so he would ask Smith to read aloud to his contracts and pamphlets, memorizing what she said. He would then recall it in detail during the meetings.

Watching her father conduct business shaped Smith’s learning and teaching style. She realized how much she had absorbed through these hands-on experiences. She now structures her classes by having students apply lessons from the textbooks to real-world scenarios.

For example, in her Intro to Business class, she assigns students a 10-page paper to complete as a group, with members playing roles like project manager, compiler, proofreader, and delivery person. Inevitably, challenges arise, and students must problem-solve as a group to deliver the paper on time.

“They are all surprised at the challenges they encounter to get that 10-page paper in,” Smith says. “These are things you will encounter in the real world. With my father, I saw all that. Being in corporate America, I saw all that. This assignment is a wake-up call to them.”

Off to China and Out of Her Comfort Zone

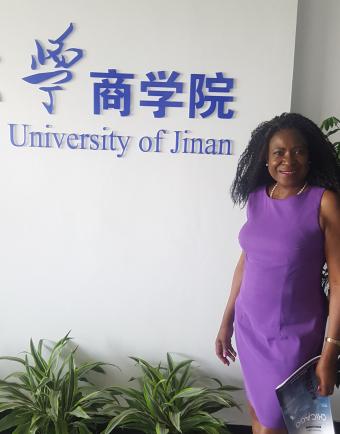

At the end of the spring 2018 semester, Smith and her husband traveled to China. She had been invited to the University of Jinan to guest-lecture on leadership, international business, and diversity in communications.

Smith based her lectures around communicating in diverse cultures, advising students to read about a country before they visit, especially to avoid social blunders. “Like if you go to Japan,” she explains, “They want you to belch at the table. Here in America, your mother would not be very happy if you do that.”

One student asked her the biggest difference between Chinese and American students.

“The Chinese students accept what the teacher says,” Smith says. “In America, if I say the sky is blue, a student will say, ‘No, it’s not.’ American students are taught not to accept everything just because the teacher says it. No matter what I said, the Chinese students nodded their heads and wrote it down. That was very enlightening to me.”

In her classes, she learned that “we are more alike than we are different,” she says. “People are people. They love their children too, just like we do. We need to practice patience and understanding with each other. ‘There is more that unites us than things that separate us.’ Those were my parting words to them.”

Following her lectureship, she and her husband traveled in rural China and to Beijing, where they visited the Great Wall, the Forbidden City, and Tiananmen Square.

“It was a culture shock to me,” Smith says as she scrolls through photos on her phone, pointing out every detail that had enlightened her about China. “I expected to see depressed people. It was a beautiful country. The architecture was phenomenal. They were very warm and welcoming, very friendly.”

She and her husband proudly “lived like locals” by taking public transportation and trying new foods. “The Chinese food is not the food they eat here,” she says. “Everyone at some point should try to get out of their comfort zone to visit another culture.”