Undocumented Immigrant Achieves Dream of Attending College

Told “no” too many times, Saul Mejia gets the chance to achieve his academic dreams at Community College of Denver

“You’re molded to grow up like an American citizen,” says Saul Mejia, 27, an undocumented immigrant from Mexico who grew up in Texas and Georgia. “As you get older, you start realizing you’re a little bit different. You start realizing that you need a social security number.”

When he approached a guidance counselor about helping him go to college, she told him to instead focus on the job he already had in landscaping. “’The landscaping business is a multi-billion-dollar industry,’” he remembers her saying. “I know she didn’t mean it, but that comment destroyed me. It was like she was giving up on me.”

Mejia graduated high school in 2010 and fell into a deep depression. He had applied to four colleges in the southeast U.S., and just one accepted him — on the condition that he prove he had $30,000 in his bank account to pay for tuition. He couldn’t prove it, so he didn’t go to college.

His depression lasted until Mejia’s brother called him to help with his plumbing business in Denver. Mejia moved to Colorado, quickly fell in love with the culture, and decided to make the city his new home.

The Good Samaritan Who Changed His Life

Mejia had been waiting in line since 3 a.m. on Sept. 24, 2015, to try to get a ticket to see Pope Francis in New York. When he didn’t get a ticket, a good Samaritan gave him one. A video of the interaction went viral, and soon Univision Denver was calling Mejia to do media interviews. When they found out he was an undocumented immigrant, they offered to get him a lawyer. Mejia didn’t need a lawyer, but he kept Univision’s contact information close by.

Months later, Mejia was alone watching the local news, and a story came on about college.

“I saw it and started crying,” Mejia remembers. “That’s something I always wanted to do. I was a host at a restaurant where they were exploiting me for my work. You feel like you’re against the wall with a knife against your chest. Seeing that news story reminded me of that.”

Mejia called his contact at Univision and asked for help getting into college. Three days later, Univision created a news story about Community College of Denver (CCD), and how it supported undocumented immigrants. They interviewed Mejia, and in so doing, put him in touch with (Ivonne) Andrea Kossik, assistant director of scholarships at CCD.

Kossik worked hard to help Mejia. She helped him overcome his ingrained skepticism to persevere through the process of supplying paperwork; though it was a challenge to enroll, Mejia is now in his second year at CCD studying communications.

He even earned scholarships and had to pay very little tuition to attend.

“I’m very happy for all the support CCD gives,” Mejia says. “Their scholarship system is designed to accept people like us with our challenges. It’s amazing that they take us into consideration.”

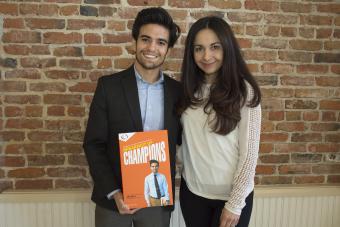

Mejia plans to graduate in May 2019 with an Associate of Arts degree. He then plans to enroll in one of Colorado’s four-year universities and hopes to one day become a broadcast journalist.

“CCD is doing a magnificent job of helping the undocumented immigrant community,” he says.

DREAMers United at CCD

“I have never known what it’s like not to be discriminated,” Mejia says. “But when you’re at CCD, race is the last thing you look at.”

Mejia raves about the diversity at CCD, one of the most diverse colleges in Colorado, and how exposure to students from other countries and cultures has opened his mind.

“In my first English class at CCD, it was my first time interacting with so much diversity,” Mejia says. “If it had been a room full of Latinos, we could potentially fall into seeing things in one lens. In my classes, I’m able to open up my mind to different things and different worlds.”

The diversity of the student body propelled Mejia into DREAMers United, a student-led organization that helps undocumented immigrants. Through DREAMers United, Mejia connects with students facing the same challenges he faced not long ago.

“I see myself in these students,” Mejia says. “I wish I would have found someone like me while I was in high school.”